One of the most frequent points of friction I encounter with procurement teams is the disconnect between the assembly line and the raw material warehouse. A client will look at our sewing floor—flexible, modular, capable of switching styles in minutes—and ask, "If you can sew 50 bags in an hour, why is your Minimum Order Quantity (MOQ) set at 500?"

The answer lies not in our ability to cut and sew, but further upstream, in the rigid constraints of our material suppliers. As a production manager, I don't just manage my factory's output; I manage the input constraints of dye houses, weavers, and chemical plants. Understanding these "upstream minimums" is critical for any buyer trying to negotiate lower volumes without sacrificing custom specifications.

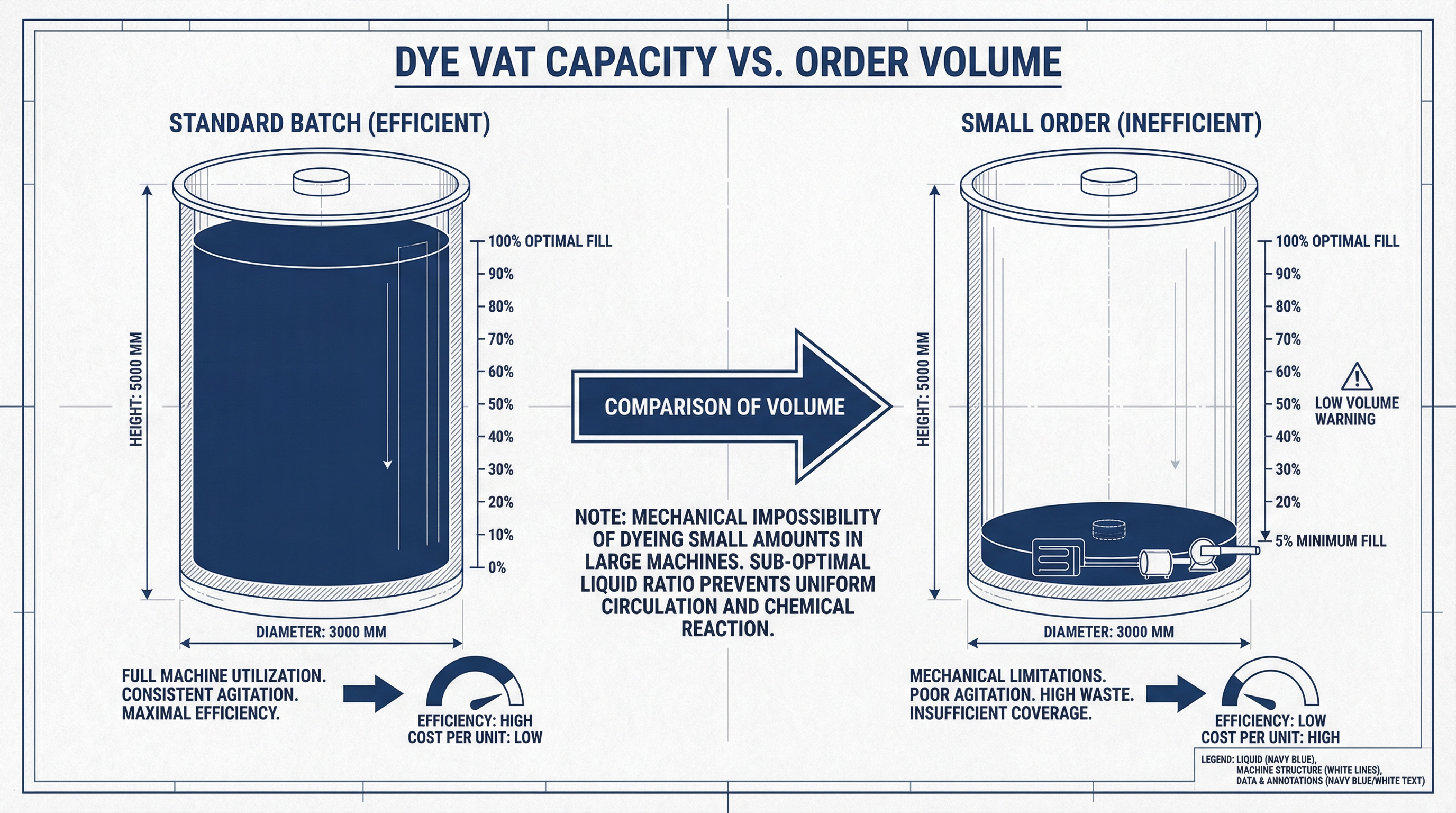

The Physics of the Dye Vat

The most common bottleneck for custom-colored textiles is the dye vat itself. Industrial dyeing is not a continuous process like printing; it is a batch process. Fabric is loaded into a pressurized vessel—a "jet dyeing machine"—where it circulates in a heated dye liquor.

These machines have a physical minimum capacity. A standard industrial jet dyer might be built to handle 200kg of fabric. If we load only 20kg (enough for your 50 bags) into that machine, the liquor ratio becomes too high. The fabric will thrash around violently, leading to pilling, uneven color absorption, and "rope marks" (permanent creases). To run that small batch successfully, we would still need to fill the vat with the standard volume of water and chemicals, wasting 90% of the energy and dyes.

In practice, this is often where Upstream Material Minimums decisions start to be misjudged. Buyers assume we can just "mix less dye." But the machine's mechanics demand a specific volume to function. If we force a small batch, the cost per meter skyrockets, or worse, the quality degrades to an unacceptable level.

The Tyranny of the Fabric Roll

Even if you choose a stock color, we face the constraint of the "roll." Fabric mills do not sell by the meter; they sell by the roll, which typically ranges from 80 to 120 meters depending on the weight and weave. Once a roll is cut, it becomes "dead stock" if not fully utilized.

Let's say your design requires 1.2 meters of fabric per unit. An order of 50 units consumes 60 meters. If the standard roll is 100 meters, we are left with 40 meters of remnant fabric. This remnant is too short for most other production runs and too long to simply discard without financial loss. Unless you are willing to pay for the entire 100-meter roll (effectively doubling your material cost per unit), we cannot accept the order.

This constraint compounds when multiple materials are involved. Your backpack might need 600D polyester for the body, 210D nylon for the lining, and air-mesh for the straps. Each of these comes from a different sub-supplier with its own roll length minimums. The final product MOQ is effectively determined by the "highest common denominator" of these upstream constraints.

The "Stock vs. Custom" Decision Matrix

When we quote an MOQ, we are essentially communicating the point at which these upstream inefficiencies neutralize. To navigate this, procurement professionals have two distinct paths:

1. The "Stock Material" Path: If you can accept standard colors (black, navy, grey) and standard materials, we can often lower the MOQ significantly. This is because we are likely drawing from a "communal" roll that is being used for multiple clients simultaneously. The waste is shared, or rather, the utilization is optimized across the factory's aggregate demand.

2. The "Custom Material" Path: If you require a specific Pantone match or a specialized eco-coating, you trigger a dedicated production run at the mill. Here, the MOQ is non-negotiable because it represents the minimum batch size of the raw material itself. For a custom-dyed rPET fabric, the mill might require a minimum of 3,000 meters—enough for 2,500 bags. Ordering 500 is simply not an option unless you pay a massive surcharge to cover the mill's setup and waste.

For a broader understanding of how these material constraints integrate with other cost factors, refer to our guide on What Is the Minimum Order Quantity (MOQ) for Customized Corporate Gifts?.

Ultimately, a flexible assembly line cannot cure a rigid supply chain. When you push for lower MOQs on custom goods, you are not just asking for a favor; you are asking the factory to defy the physical and economic laws of their material suppliers. Recognizing this boundary is the first step toward more realistic and successful procurement planning.

Related Articles

The Opportunity Cost of Stopping the Line: Why Factories Reject Small Orders

Why would a factory refuse your order even if you offer to pay a higher unit price? A production manager explains the hidden economics of 'Machine Downtime' and why stopping a high-speed line for a small run is a financial loss.

The Real Timeline of Custom Manufacturing: A Procurement Guide for Singapore Enterprises

Stop guessing your event timeline. A 15-year supply chain expert reveals the hidden bottlenecks in custom manufacturing—from mold stabilization to multi-SKU risks.

Need Professional Corporate Gifting Advice?

From material selection to logo printing and logistics, our team is here to provide expert guidance for your needs.

Contact Us Now