In the world of precision injection molding with virgin plastics, the "Golden Sample" is the holy grail. It represents the perfect execution of a specification: exact Pantone match, zero flash, uniform texture. Once signed off, it becomes the immutable standard against which every single unit of a million-piece run is measured. If a production unit deviates from the Golden Sample, it is a defect.

However, when we transition to sustainable supply chains involving bio-composites (like wheat straw PP) or natural fibers (like bamboo or cork), applying this binary "match or reject" logic is not just impractical—it is a procurement liability. In practice, this is often where customization process decisions start to be misjudged, leading to mass rejections of perfectly functional, eco-friendly stock, or worse, strained supplier relationships that threaten delivery timelines.

The Myth of Uniformity in Nature

The fundamental error lies in treating organic matter like synthetic polymer. A virgin plastic pellet is chemically engineered for consistency. A bamboo fiber or a wheat stalk is grown, harvested, and processed under varying environmental conditions. Seasonality, soil composition, and harvest timing all introduce inherent variations in color, grain density, and texture absorption.

When a procurement team demands a single Golden Sample for a bamboo-fiber bento box, they are essentially asking for a snapshot of a specific harvest batch. If the mass production run occurs three months later using a different batch of raw bamboo flour, the natural base color may shift slightly from a creamy beige to a warmer tan. If the Quality Control (QC) inspector is armed only with the Golden Sample, they are forced to flag the entire shipment as "non-compliant," despite the product being chemically identical and structurally sound.

The "Uncanny Valley" of Eco-Plastics

Ironically, if a bio-composite product looks too uniform, consumers often perceive it as "fake" or "greenwashed." A slight variance in texture or visible fiber flecks actually reinforces the authenticity of the sustainable material claim. The goal of QC for eco-materials should not be to eliminate variance, but to manage it within an acceptable aesthetic window.

The Solution: The "Limit Sample" Protocol

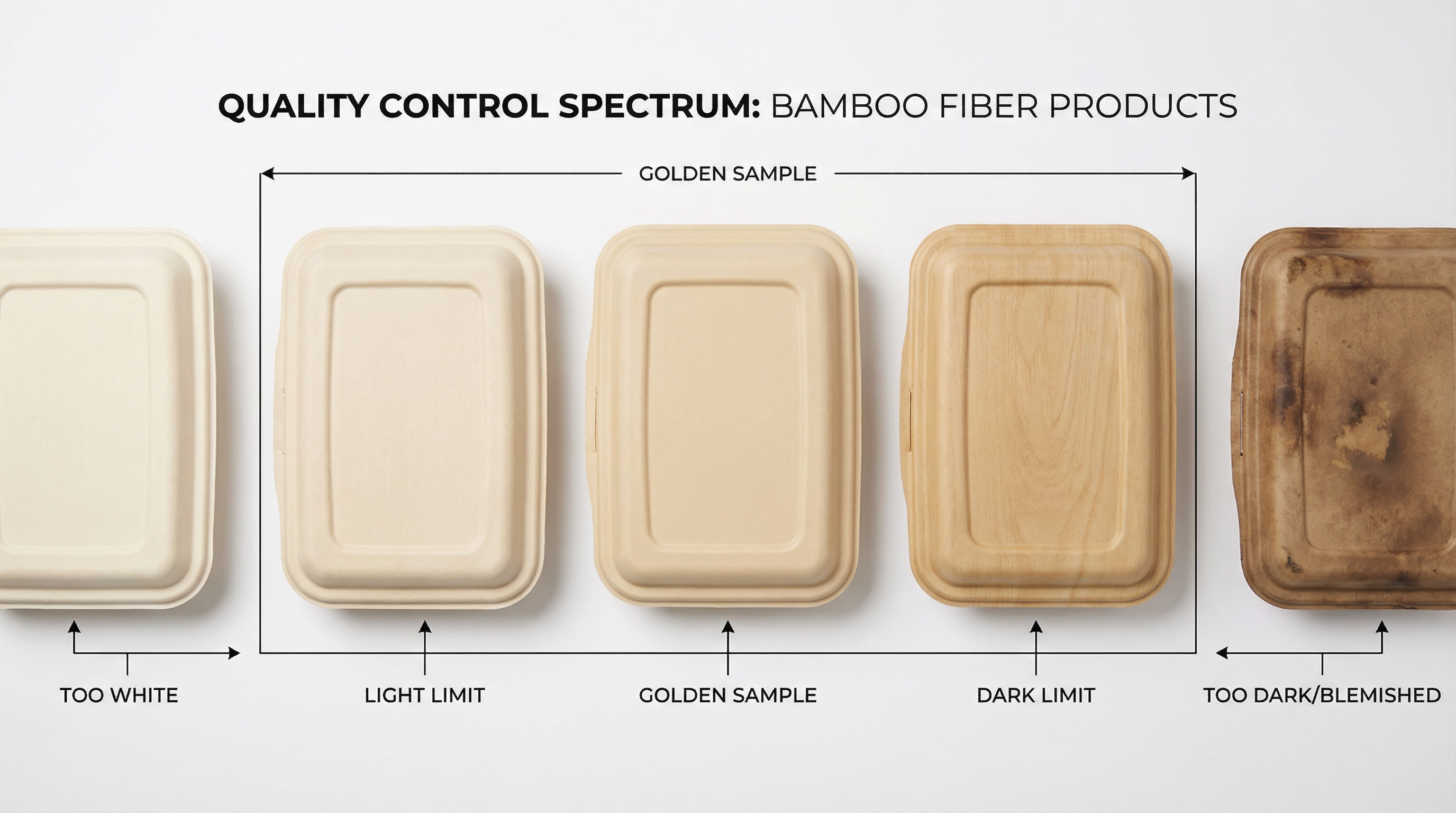

To mitigate this risk without compromising on brand integrity, we advise shifting from a single Golden Sample to a "Limit Sample" (or Range Sample) Protocol. Instead of signing off on one perfect unit, the stakeholder approves a set of three samples:

- Target Sample: The ideal aesthetic outcome (the traditional Golden Sample).

- Light Limit: The lightest acceptable shade or finest acceptable texture.

- Dark/Rough Limit: The darkest acceptable shade or coarsest acceptable texture.

This triad defines a "Zone of Acceptance." Any production unit falling between the Light and Dark limits is deemed compliant. This approach acknowledges the material reality of products like our wheat straw cutlery sets or bamboo tumblers, where fiber distribution is random and non-homogeneous.

Implementing this protocol requires upfront communication. It means the "Customization Process" is not just about logo placement, but about defining the material's permissible character. For a deeper dive into how different branding methods interact with these material variances—for example, how laser engraving reacts differently to varying bamboo densities—we recommend consulting our guide on Custom Branding Eco-Products.

Operationalizing the Shift

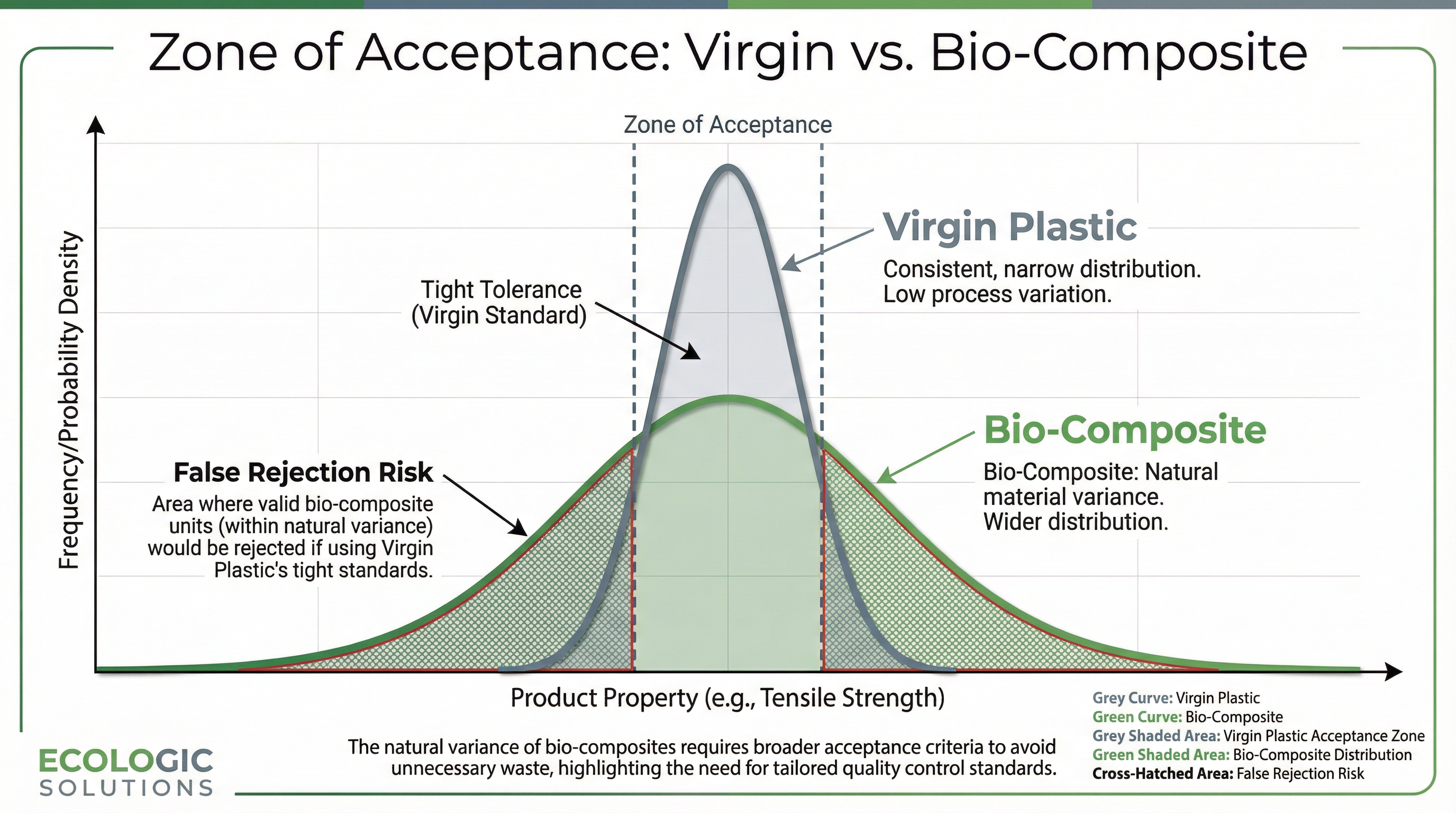

For factory-side project managers, the Limit Sample protocol is a critical defense against subjective rejection. It transforms a qualitative argument ("This looks too dark") into a quantitative assessment ("This unit is within the approved Dark Limit").

For the buyer, it ensures supply chain resilience. By accepting a controlled range of natural variance, you reduce the scrap rate at the factory level (waste is the enemy of sustainability, after all) and ensure that your order is not held up by unrealistic aesthetic policing. It aligns your procurement standards with the very ethos of the product you are buying: natural, imperfect, and sustainable.

Figure 1: The statistical risk of "False Rejection" when applying virgin plastic tolerances to bio-composite materials.